Reading "The Wages of Destruction" by Adam Tooze

- Christopher Soelistyo

- Jan 5, 2022

- 58 min read

Updated: Jan 9, 2022

How was it possible that for the second time in a generation, Germany should have embarked on a campaign of conquest and destruction, aimed at restructuring global power, that ended in defeat? This is the fundamental question posed by economic historian Adam Tooze in one of his first major books, The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy. He attempts this by tracing the economic history of the Third Reich - from its inception in 1933 to its implosion in 1945 - and showing how economic realities impacted significant decisions taken by the Nazi leadership, above all, the decision to go to war in September 1939.

The book is revisionist in nature, a status well attested to by its cover reviews: "This book will change the way we look at Nazi history" (Sunday Telegraph), "A powerful and provocative reassessment of the whole story" (Richard Overy), "Adam Tooze has rewritten the history of the Second World War" (History Today), "One of the most important and original books to be published about the Third Reich in the past twenty years" (Niall Ferguson). Alas, I am insufficiently versed in the field to know how groundbreaking Tooze's ideas were when the book was published in 2006. However, I'll try my best to summarise - and inevitably simplify - some of the key conclusions of the book (as I have understood them), structured in the form of a few questions.

Note: This review is rather long! If you would like a summary of the main points, skip to Section VI: Reflections.

I: Why Did Hitler Go To War in 1939?

I.I: Ideology

The alpha and omega of Adolf Hitler's thinking was his view of the world as a racial struggle for survival in which the weak would be consumed by the strong. In this respect, he viewed the ultimate enemy of the Aryan people as the Jews, to whom he attributed the catastrophe of World War I, as well as the international alliance of "world Jewry" that was to face him in World War II. Unless Germany re-emerged from the ashes of World War I as a racially pure great power endowed with military might, the efforts of international Jewry would precipitate the destruction of the German nation itself.

The problem was that the pre-eminent powers of the world were, in this world-view, under Jewish control, whether they were the Jewish bankers of the City of London, or those pulling the strings in Washington (eventually to culminate in the leading figure of the world Jewish conspiracy, Franklin D. Roosevelt). How was Germany to muster the necessary strength to compete with Britain - keeper of the world's largest empire - and the United States - the world's largest economy - especially under the crushing burden of post-Versailles reparations and arms limitations?

In the Introductory chapter, Tooze describes two opposing answers to that question, associated most closely with the twin figures of Adolf Hitler (1889 - 1945) and German statesman Gustav Stresemann (1878 - 1929). As foreign minister of the Weimar Republic from 1923 to 1929, Stresemann embarked on a policy to revive Germany's economic might that involved, not conflict, but cooperation with the powers victorious in World War I. Though Stresemann was an ardent nationalist who appreciated the utility of military force, the searing experience of the German defeat in World War I had "shook his confidence in military force as a means of power politics, certainly as far as Germany was concerned" (p.4). This belief was reinforced by the post-Versailles reality, where Germany saw its military shackled with constraints. Instead of military force, Stresemann's revival of Germany would be based above all on industry, finance and trade.

The situation post-Versailles was that Germany owed crippling reparations to Britain and France, reparations that - with Germany's current condition - the Germans would never be able to pay. Simultaneously, Britain and France were indebted to Wall Street, from which they had borrowed loans to finance the war effort. The US Congress was unwilling to budge on these war loans, and Britain and France - owing to public opinion in both countries - were unwilling to budge on reparations as well. Moreover, German society had suffered a severe bout of hyperinflation from 1921 to 1923, powered by the German policy of printing banknotes in order to service reparations obligations. As such, by the end of 1923, the Papiermark had lost virtually all of its value. It was from this maelstrom that Stresemann engineered his dramatic turnaround of the German economy.

As part of his strategy for revival, Stresemann arranged for German corporations to also attract loans from Wall Street - this would be forthcoming given the promising strength of Germany industry (the "unlimited respect of the world for the achievements of Germany industry and of the German trader" (p.5)). Germany would use part of these loans to finance its reparations obligations, which would henceforth circle back to the United States in the form of Britain and France servicing their war debts.

Furthermore, in order to secure American claims on German business, the United States would put pressure on France and Britain to ease their reparations demands should Germany not be able to fulfil them after servicing their debts to American creditors. Thus Stresemann would use the United States as a lever to pry away British and France reparations demands, whilst at the same time securing a source of financing for German industry. Eventually, this strategy appeared to be working. By 1931, Germany's foreign debt to the United States stood at 8.4 billion Reichsmarks, by far the largest of any creditor. Indeed, by 1928, it was not the Germans, but the Americans - most notably Benjamin Strong, chairman of the US Federal Reserve - who were pushing for a renegotiation of Germany's reparations obligations.

However, Stresemann's strategy was not to last. It had been premised on an increasingly activist American role in Europe - in particular, to achieve the renegotiation of the terms of the Versailles treaty - but this was was not as forthcoming as Stresemann had hoped. For one, by the late 1920s, the administration of Herbert Hoover was still unwilling to draw an explicit linkage between reparations payments to Britain and France, and inter-Allied war debts owed to the United States; this was the linkage on which Stresemann's involvement of the Americans had been premised. Moreover, the Great Depression precipitated an isolationist turn in the United States, culminating in the Smoot-Hawley Act of March 1930, which imposed significant tariffs against European imports. No longer could America play the balancing role that it needed to.

The collapse of Stresemann's "Atlanticist" strategy, accompanied by the untimely death of Gustav Stresemann himself in October 1929, thus opened the way for an alternative approach, one that associated itself not with liberal internationalism, but with hyper-aggressive militaristic nationalism. Its most significant proponent was Adolf Hitler.

Hitler espoused an "embattled" ideology that saw the only chance of Germany's survival in its embrace of ruthless struggle against its enemies. For him, the decisive factors in world history were "not labour and industry, but struggle for the limited means of sustenance" (p.8). Britain could sustain itself through free trade only because it had already conquered a vast empire through military force. Germany, on the other hand, absent this luxury, would be forced to secure a decent standard of living by acquiring "living space" (Lebensraum), which could only be achieved by "warlike conquest". The natural space from which to carve out this Lebensraum were in the lands to Germany's east, which included central Europe and, eventually, the Soviet Union.

War was the only option. If Germany tried to build its strength via industry and trade, it would merely suffer a repeat of World War I, which Hitler (and Stresemann) believed was deliberately initiated by Great Britain to "cripple Germany as an economic and naval competitor" (p.8). A violent imperial competition was inevitable, so the German people should not convince themselves otherwise.

But why did Germany need this "living space" anyway? A few clues might be found in Hitler's thinking about the United States of America, which featured prominently in his "Second Book" (written after Mein Kampf but not published during his lifetime). Even though America was not yet a significant military actor in Europe, its sheer economic power and affluence changed the parameters of everyday life on the Continent. In his own words:

"The European today dreams of a standard of living, which he derives as much from Europe's possibilities as from the real conditions of America. Due to modern technology and the communication it makes possible, the international relations amongst peoples have become so close that the European, even without being fully conscious of it, applies as the yardstick for his life, the conditions of American life..." (p.10).

Already here we see Hitler's recognition of America's superiority in the economic sphere. In particular, he finds its source in America's own Lebensraum, as evidenced by its dominance in the motor vehicle industry (of particular fascination to Adolf Hitler). What enabled the Fordist methods of American mass-production was the scale of the continental United States. The much larger population of America (125 million in 1933, compared to Germany's 65 million) meant that the United States contained a larger "internal market", ensuring American industry a larger amount of guaranteed internal sales, thus endowing it with the advantages of economies of scale. This advantage was compounded by America's relative abundance of raw materials, a function of America's "relationship of surface area to the population", which was "vastly superior" to that which existed in Europe (p.10).

Furthermore, America's economic and industrial dominance carried important strategic implications. Hitler believed that it threatened the "global significance" of European countries, threatening to reduce them all to the status of "Switzerland and Holland" (ouch). The European response to the United States "had to be led by the most powerful European state, on the model of the Roman or British empires" (I wonder which state he had in mind?). Only then could Europeans attain the standard of living enjoyed in the United States.

It was this imperative for Germany to match the economic and industrial might of America that necessitated its acquisition of Lebensraum. The process would entail the conquest of lands in the east, and, in order to make room for the German people, the concomitant removal of their inhabitants. Hitler seems to have "envisioned a more or less systematic series of steps starting with the incorporation of Austria, then the subordination of the major Central European successor states, most notably Czechoslovakia, culminating in a settling of accounts with the French" (p.9). This latter step was meant to neutralise potential opposition to Germany's plans of expansion, clearing its path for a drive to the east.

In this respect, the cooperation - or at least acquiescence - of Britain was also crucial. Hitler firmly believed that to seek influence in overseas territories would run Germany straight into conflict with the British Empire. However, Germany could avoid this threat by pursuing a strategy of Continental expansion. Thus Hitler's strategic conception in the 1920s and 1930s was premised on the ability of Germany to attain a dominant position in Europe without coming into conflict with Britain. In fact at this point, Hitler considered that Britain might even join Germany as an ally in its eventual struggle against the United States.

This world-view provides a rationale for going to war. Germany needed additional Lebensraum in order to become a great power - which was needed to protect Germans against the machinations of world Jewry. It would source this Lebensraum in the east, and it would achieve this by means of violent conquest and the forced removal of millions of people. But why did Hitler choose that particular moment - September 1939 - to launch his strike? Tooze contends that, in essence, this was because that particular time made the most sense.

It made the most sense for two reasons: because Germany had reached the apex of its relative strength in terms of armaments - in relation to its prospective adversaries - and because the global diplomatic situation at this time was most favourable.

I.II: Armaments

Armaments are, of course, the key to any war effort. Yet as far as armaments spending goes, the Third Reich had always faced significant problems - particularly in relation to Germany's balance of payments. In other words, Germany's dependence on imports of raw materials - which increased as German industry recovered after Great Depression - coupled with its perennially low export levels, caused a persistent crisis of foreign currency that stymied efforts to import the materiel necessary to sustain a truly significant armaments drive.

By 1938, the foreign exchange problem had become acute. One symptom of this was the difficulty faced by the Nazi Party in convincing Germany's Jewish population to emigrate the country - after an initial burst in 1933, the numbers had stagnated to roughly 20,000 emigrants per year. To explain this difficulty, Tooze claims that "the most important single obstacle was clearly the extremely high cost of leaving Germany ... [which was] in turn dictated by the same problem that afflicted virtually every other aspect of Nazi policy, the shortage of foreign exchange" (p.275). German Jews could not be convinced to leave the country without adequate savings of foreign exchange to take with them. Here already we can see the Third Reich struggling to fulfil its ideological objectives in the face of economic realities.

In the realm of armaments, this glaring scarcity of foreign exchange was no less apparent, a state of affairs made all the more threatening by the accelerating arms programmes of Germany's potential adversaries (Britain, France and the United States) - which were in turn at least partially a response to Germany's behaviour post-1933.

Ever since the inception of the Third Reich, its foreign and domestic policy had been based on the aggressive pursuit of the Nazi Party's ideological goals. In the sphere of industry, this meant putting armaments production at the top of the priority list. Indeed, in their first six years in power, the Nazis managed to boost military spending as a share of national output from less than 1 percent to almost 20 percent, constituting the largest peacetime shift of resources to military uses by any capitalist state in history (pp.659, 660).

Nazi Germany also pursued an aggressive foreign policy. In 1938, this culminated in both the forced Anschluss (lit. "joining") of Austria to the Third Reich in March, as well as the annexation of the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia in October (in line with the strategic contemplations of Hitler's Second Book). The Anschluss took place without must protest from the Western powers. However, this move ignited fears of a wider war on the European continent, placing - as it did - German troops on three sides of the western half of Czechoslovakia (where the Sudetenland was located). These tensions culminated in the "May Crisis" of 20-21 May, when false rumours of an impending German attack galvanised the Czechoslovak state to mobilise military reservists and call on the support of its allies - Britain and France. Crucially, this is where Britain and France established a show of force, warning Germany that they would come to Czechoslovakia's aid should the Germans attack (p.247).

Though Britain and France eventually permitted Hitler to take the Sudetenland anyway (in the Munich agreement of 30th September), the May Crisis had delivered a message that the Nazis would never forget. From this crisis onward, Hitler "began seriously to contemplate the need for a major war in the West, as a prelude for his drive against the Soviet Union [whereas previously he had hoped at least for Britain's acquiescence]". This was "the essential lesson that was learned in Berlin by the early summer of 1938", regardless of what later happened at Munich. The Third Reich had to "regard the British Empire as a force opposed to Hitler's dream of conquest in the East" (p.248). Moreover, German military planners had always envisioned that in the case of a war with Britain and France, these two foes would be assisted by the enormous economic power of the United States, forming once again the formidable alliance that had defeated Germany in World War I.

Source: Never Was Magazine

The Third Reich after the incorporation of Austria and the western half of Czechoslovakia. After the Anschluss, Austria began to be referred to as "Ostmark" in Nazi propaganda to symbolise its status as the "eastern march" of the Reich. The Reich's Czechoslovak captures were split into the Sudetenland, which was incorporated into the Reich, and the protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

The crucial point here is that by the spring of 1938, these looming enemies were all engaged in substantial rearmament - galvanised by the aggression of Germany as well as Italy's invasion of Ethiopia in 1935/36 and the launch of Japan's invasion of China in 1937. Moreover, once they got started, Germany would have no chance of keeping up. In the naval arena, contemporary sources suggest that the British Royal Navy had outspent the German Kriegsmarine by 30 percent since 1933. Hence Britain continued to widen its already overwhelming advantage in warships. Even more threatening was the United States; on 17th May 1938, President Roosevelt signed into law the $1.15 billion Naval Expansion Bill, which "ensured that the United States outspent any of its rivals in the worldwide naval arms race" (p.249). At roughly the same time, London also embarked on an ambitious programme to expand its air fleet (producing 12,000 modern combat aircraft over the next two years), and France also launched its own 12-billion-franc effort to strengthen its military, of which 9 billion francs would be committed to producing 4,700 new aircraft (p.250, this source). Moreover, in the aftermath of the Munich agreement, US President Roosevelt was taking a harder line against Germany. By the end of 1938, he had accepted a French purchasing mission to buy as many as 1,000 American combat aircraft (Roosevelt talked of supplying the Western powers with as many as 20,000). At the same time, he imposed a 25 percent punitive tariff on German imports, a measure "viewed in Berlin as tantamount to a declaration of economic war" (pp.306, 307).

However, Germany would not sit idly either. After the May Crisis, Hitler ordered a renewed, massive armaments effort that would ready Germany for war with the Western powers. But could the German economy handle it?

Already in June 1936, the military planners had envisioned a series of expansion projects that would endow the Wehrmacht, by October 1940, with 102 divisions, consisting of more than 3.6 million men. Impressive as they were, the expansion programmes would "stretch the Germany economy to its limit". Equipping a wartime force of 102 divisions within four years would require "a huge acceleration in military spending". As spelled out by the German Army's General Friedrich Fromm, if the expansion plan were to go forward, the army alone would need to spend 9 billion Reichsmarks per year, twice the figure that had been previously agreed for the entire Wehrmacht. Moreover, even assuming that sufficient foreign exchange could be obtained (a dubious assumption at best), the armament effort would require a massive increase in production capacity - and the question had to be faced: once the Wehrmacht's targets were met, what would be done with this spare capacity? The plants could either by converted to civilian production (at high cost) or be kept spinning for war production, which would produce an enormous surplus to requirements (unless the Wehrmacht were to somehow find itself at war...) (p.213).

After the crisis of May 1938, Hitler ordered this full expansion plan moved forward to April 1939, as well as ordering the army to maintain stocks sufficient to cover three months of fighting (this tripled the army's request of extra steel from 400,000 tons to 1.2 million tons from 25th - 31st May). In the aftermath of the crisis, the Luftwaffe also committed itself to a massive expansion plan, with its commander Hermann Goering ordering a fleet of no less than 7,000 Ju-88 bombers (p.250). These armament plans drastically altered the shape of the German economy at the expense of household consumption, which now stagnated or fell (between March and July 1938, the steel available for non-Wehrmacht purposes was cut by 25 percent). The main factor constraining the German economy's growth was, as usual, "the external limitation imposed by the balance of payments" (p.254).

Despite the enormous stresses that this produced in the German economy, figures like Goering saw these sorts of efforts as vital to Germany's survival. On 8th July, during a major address to figures in Germany's aircraft industry, he claimed that Germany was facing the possibility of a "world war" in which its enemies - France, England, Russia and America - would be able to summon an "immense reservoir of raw materials". Given the scale of this threat, they now faced the "greatest hour of destiny ever since there has been a German history" (p.255).

In the aftermath of the Sudeten crisis in September 1938 (which resolved itself in the Munich agreement), Goering announced an expansion plan of even larger scale "compared to which previous achievements are insignificant" (p.288). The army would continue its enlargement begun in 1936 (now claiming the need for a quarter of Germany's entire production of steel - 4.5 million tons - in 1939). Meanwhile, the air force would undergo a five-fold expansion, reaching a strength of more than 21,000 combat aircraft (note that during World War II, the Luftwaffe reached a maximum strength of barely 5,000 aircraft in December 1944). In addition, the navy launched a renewed effort to compete with Britain's Royal Navy, endeavouring to reach a strength of 797 vessels (at a cost of 33 billion Reichsmarks) by 1948. As with the Luftwaffe plan, the infrastructural costs would be enormous (p.288).

In Tooze's view, it was clear that these armaments plans "never had any chance of being realized" due to their immense overestimation of Germany's industrial capacity (especially considering its balance of payments issues). Indeed, by 1939, the Reichsbank - Germany's central bank - was informing Hitler that "gold or foreign exchange reserves of the Reichsbank are no more in existence" (p.301). It had gotten to the stage where Goering and Hitler were even exhorting the German population to "export or die", even if a rise in exports would entail a retreat in their armaments ambitions. By late 1938/mid-1939, armaments targets were being cut across the board (530,000 to 300,000 tons of steel for the army; 61,000 to 13,000 Model 34 machine guns; 840 to 460 light field howitzers; 1,200 to 600 medium battle tanks, and more). The Luftwaffe plan could only save its 21,000-aircraft target by shifting production to later years (pp.302, 303).

The fundamental issue, then, was that with Germany facing a British-French alliance (ironclad after Berlin's full-blown invasion of Czechoslovakia in March 1939), which enjoyed the full support of the United States, "any conventional strategic analysis suggested that Germany was outmatched" (p.309). Neither was the panacea for this issue - a strategic condominium with Italy and Japan - within the reach of German diplomacy (in any case, Japan was tied down in China). The Wehrmacht's chief economist, Major-General Georg Thomas, put these issues in stark terms in May 1939: in the coming year, Britain, France and the United States would be able to outspend Germany and Italy in military expenditure by a margin of at least 2 billion Reichsmarks. Furthermore, the "democracies" would suffer less crippling burdens on their economies; in 1939, Germany was spending 23 percent of its national income on the Wehrmacht, whereas for France the figure was 17 percent, for Britain, 12 percent, and for the United States, only 2 percent. Factoring in the raw material reservoir of the British Empire and the industrial capacity of the United States, it was clear that Germany's disadvantage would be overwhelming.

In other words, the longer Germany waited, the worse its military prospects would become. On the other hand, by the summer of 1939, Hitler knew that Germany had assembled "both the largest and most combat-ready army in Europe, as well as the best air force". He was certainly in a position to easily complete the next stage of his plans - the conquest of Poland - even though a potential clash with Britain and France was still daunting. According to Tooze, this state of affairs meant that "it was possible ... to construct a rationale for war in the autumn of 1939, considering only the dynamics of the armaments effort. If war was inevitable, as Hitler clearly believed it was, then the Wehrmacht had little to gain from waiting" (p.316). As he wrote to Italian dictator Benito Mussolini in March 1940:

"Since the introduction of conscription in England [in the spring of 1939] it was perfectly clear that the decisive circles in the British government had already decided on the next war against the totalitarian states ... In light of Britain's intended armaments effort, as well as considering England's intention of mobilizing all conceivable auxiliaries ... it appeared to me after after all to be right ... to begin immediately with the counterattack [Abwehr], even at the risk of thereby precipitating the war intended by the Western powers two or three years earlier. After all Duce [Mussolini's title], what could have been the improvement in our armaments in two or three years? As far as the Wehrmacht is concerned, in light of England's forced rearmament, a significant shift in the balance of forces in our favour was barely conceivable. And towards the east the situation could only deteriorate [perhaps a reference to the March 1939 Anglo-French security guarantee to Poland?]" (p.317).

As Hitler made clear in his letter to Mussolini, it was the deteriorating armaments situation that compelled the Wehrmacht to attack sooner rather than later; after all, there was nothing to gain by waiting. This reality, coupled with the diplomatic windfall ushered by the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact of 23rd August 1939, landed Germany in an optimal position to launch war (According to Tooze, Hitler gave the first order for an attack on Poland as soon as he knew that the pact would for certain be signed in Moscow).

As a result, "Hitler chose war in September 1939 and he did so even though he knew that an attack on Poland would most likely provoke a declaration of war by Britain and France" (p.321). In writing these words, Tooze deliberately contradicts a train of historical thought that supposes that Hitler invaded Poland without the expectation that it would trigger a wider war, the implication being that if he knew what the consequences would be, he may have pulled back. Since he did expect these consequences, why did he do it? According to Tooze, it was because he had nothing to gain by waiting.

The war itself went superbly well for the Wehrmacht in its first year, as the German army conquered Poland then scored spectacular successes in the West, occupying a host of European states - including, most importantly, France - and driving the British off the continent within a matter of weeks. Germany's lightning victory in the West was an incredible coup, one that seemed to defy the material odds facing the Third Reich at this juncture - which certainly were not overwhelming in its favour. One is thus tempted into a voluntarist reading of events, where factors such as 'élan' or the 'superior fighting power' of the German troops mattered more than their material situation. As such, Tooze regards the Western campaign as posing a "major challenge to any economic analysis of World War II", in particular, his more materialist - as opposed to voluntarist - approach (p.370). He therefore devotes a chapter to analysing exactly how the Wehrmacht managed to achieve such rapid success in its Western campaign.

II: Why Did the Wehrmacht Achieve Victory in the West?

One possible explanation for Germany's incredible success in the West was that it employed a stunningly successful strategy of lightning war - "Blitzkrieg" - wielding a mechanised military machine that was tailor-made for this new way of waging war, a far cry from the attritional slogging match of World War I. This account would indeed explain the Western campaign from a material perspective (in so far as it a superior German fighting force) but it would undermine Tooze's assertion that Germany enjoyed no significant military advantage compared to Britain and France in the spring of 1940. Thus, before he presents his own explanation of Germany's victory, he delivers a critique of the Blitzkrieg hypothesis.

Ever since World War II, the term "Blitzkrieg" has become notorious. Commonly associated with the image of a mechanised force employing superior speed and power to overwhelm a stunned enemy, this term first came into use in the hands of Western journalists describing the invasion of Poland in September 1939, and was later used frequently in relation to German strategy in Western Europe.

However, Tooze - along with many other historians - regards the existence of a Blitzkrieg concept in German military thinking to be a myth (in fact, though the word has been attributed to Hitler, he himself apparently stated that "I have never used the word Blitzkrieg, because it is a very stupid word").

In particular, Tooze trains his cross-hairs on the idea that Blitzkrieg was some sort of "conscious military-economic strategy", devised by the Third Reich as an antidote to its nightmare scenario of a prolonged attritional war in the manner of World War I (which it would certainly lose). As this account goes, the Third Reich "deliberately set out to create a new kind of military organization, all clanking tanks and screaming Stukas [dive-bomber planes], designed to deliver battlefield victory at a single lightning stroke", thus "battlefield technology, military planning, diplomacy and military-economic preparation were welded together into a devastatingly effective unit" (p.371).

In reality, the German army that invaded France in 1940 was "far from being a carefully honed weapon of modern mechanized warfare". Indeed, Germany's 2,439 tanks were far outnumbered by the at least 4,200 fielded by the Belgian, French, Dutch and British armies (with the French army alone accounting for 3,254). Nor was this quantitative inferiority compensated for in qualitative terms; the German tanks deployed in 1940 were in many respects "inferior to their French, British or even Belgian counterparts". This disadvantage was mirrored in the air game; in May 1940, the Luftwaffe possessed 3,578 combat aircraft, compared to an Allied air strength of 4,469 combat aircraft, including high-quality American fighters. As such, German success "clearly cannot be attributed to overwhelming superiority in the industrial equipment of modern warfare" (pp.371, 372).

The lack of connection between Germany's military-industrial preparations and the actual course of events in 1940 is further accentuated by the fact that before September 1939, the Wehrmacht had not actually drafted a plan for an attack on France at all. When they finally did, in October 1939, the initial plan called for a "short, northerly stab towards the Channel coastline followed by an aerial campaign against Britain" - a far cry from the "Blitzkrieg" strike that actually happened (more details later). As it turns out, the Wehrmacht was forced to abandon this plan because in February 1940, two German officers were shot down over French territory carrying a briefcase of staff maps. As a result, they had to switch tack to a bold alternative plan developed by General Erich von Manstein, which had actually been rejected in December 1939 for being "absurdly risky". Given that Manstein's plan was adopted only two months before the start of the campaign, there was no way that Germany could have significantly adjusted its military-industrial preparations to account for its new strategy (p.373).

It is this strategy - as well as the unfortunate decisions of the Allies that made it work - to which Tooze attributes Germany's success in the spring of 1940. In other words, the outcome was far from preordained by Germany's pre-war preparations; there are many scenarios in which German or Allied strategy could have been different, and if this was the case, Germany might have encountered a far more arduous battle than it did.

Tooze expands this point by narrating the course of events. In the early morning of 10th May 1940, the Western front roared into life as the Germans opened with an artillery barrage on French, Dutch and German positions. At the same time, Belgian fortifications on the river Maas were seized by German special forces, accompanied by parachute landings on the outskirts of The Hague and Rotterdam. These actions, combined with the advance by German Army Group B toward the Maas river line, succeeded in luring the British Expeditionary Force and the bulk of the French army northwards to counter the German assault. The diversion had worked. Meanwhile, 100 kilometres to the south, 7 tank divisions under Army Group A wound their way undetected through the Ardennes forest, through Belgium and Luxembourg toward the French border. By 20th May, Army Group A had reached the channel, securing a position in northern France. Meanwhile, Army Group B had established a position in the Netherlands and Belgium. The British and French, who had made the disastrous mistake of moving virtually all of their forces north, were now encircled (pp.368, 389).

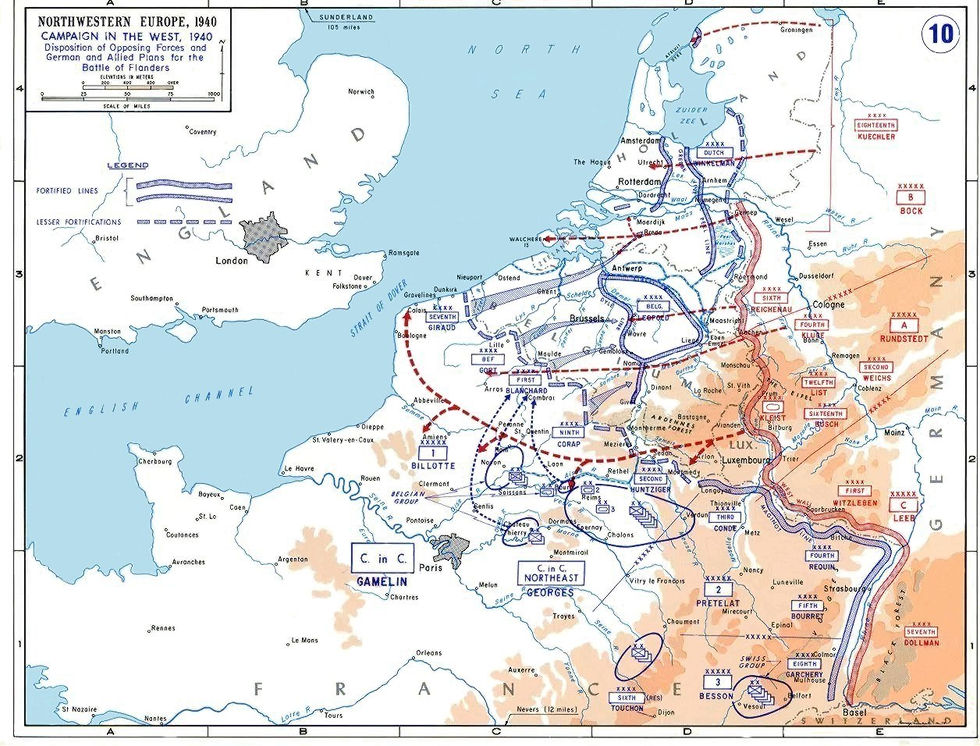

Source: Wikimedia Commons

General Erich von Manstein's attack plan for spring 1940, later referred to as the "sickle cut" (sichelschnitt) plan. Army Group B, commanded by Field Marshall Fedor von Bock, lures the Allied forces northwards while Army Group A, commanded by Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt, tunnels through the Ardennes before striking from the south.

Manstein's plan had worked to perfection: "In a gigantic scything blow Army Group A had carved out a pocket measuring 200 kilometres in length by 140 kilometres in breadth. It was the largest encirclement in military history and the yield was extraordinary. Caught between the hammer and anvil of the German attack were no less than 1.7 million Allied soldiers [of whom the Germans took 1.2 million as prisoners of war], including the entire Dutch and Belgian armies, the British Expeditionary Force and the pick of the French army" (p.369).

It was above all Manstein's brilliant plan of attack that secured victory for the Germans in 1940. However, rather than being based on some revolutionary, mechanized way of warfare, it was in fact based on a principle employed by the German army since the nineteenth century, that of Schwerpunkt, or "focal point"/"centre of gravity". This principle dictated the concentration of a superior weight of force - greater than the enemy - at a single point (though the Germans suffered a 2:1 numerical disadvantage at most parts of the line, in the Ardennes forest, they enjoyed an advantage of almost 3:1).

This concentration of force is what made the plan work, but it is also what made it extremely risky (pp.376, 377). If the French and British had held back substantial reserves - rather than committing virtually all of their forces to the north - the advance of Army Group A in the south would have been vulnerable to "counterattack, or even counter-encirclement". Indeed, the movement of Army Group A was outlandishly risky. The bulk of its armour was grouped together in the giant Panzer Group Kleist, which consisted of 1,222 tanks, 545 half-tracks and 39,373 trucks and cars, concentrated along only four narrow roads, with each of the four columns stretching 400 kilometres. The plan called for this giant mass to reach the river Maas bridges by 13th May - otherwise, the Allies would have time to react to the southern advance with force. If Allied bombers could penetrate the German fighter screen over the Ardennes, they could have wrecked unbelievable havoc among this slow-moving traffic (p.378).

Making the plan work required substantial commitments by the Wehrmacht. In order to ensure that Panzer Group Kleist could reach the river Maas on time, Germany had to commit virtually all of its remaining stocks of petrol, executing a complex logistical operation to prevent what could have been the "world's worst traffic jam". The plan also required that the German columns drive for three days and three nights without interruption, for which the sleepless drivers depended on doses of amphetamine (in the form of Pervitin, or "tank chocolate" (Panzerschokolade)). Furthermore, in order to achieve the concentration of force that it did, the Germans had to commit virtually all of their tanks and combat aircraft to the campaign; they did not keep a single Panzer division in reserve. To maintain air superiority, the Wehrmacht had also committed the vast majority of its aircraft; by the end of May, 30 percent of the Luftwaffe's aircraft had been destroyed and another 13 percent seriously damaged. In other words, if Manstein's plan had failed, Germany would have been left without the resources to continue the war (pp.376, 377).

As Tooze summarises, "if the initial assault had failed, and it could have failed in many ways, the Wehrmacht as an offensive force would have been spent" (p.380). That is to say - Germany did not achieve a lightning victory in the spring of 1940 on the basis of a superior military-industrial strategy of Blitzkrieg; in fact, it enjoyed no significant military advantage going into the campaign. What granted it victory was Manstein's extraordinarily risky plan, which paid off marvellously for the Wehrmacht but could have landed them in seriously hot water. Tooze thus rejects both the voluntarist reading of 1940 that posits that success depended on "the uncanny élan of the German army" or "the unwillingness of the French to fight", and the Blitzkrieg explanation that supposes that Germany did in fact have a superior fighting force (p.379). What saved it was an improvised gamble, a "one-shot affair" that could not be reliably reproduced elsewhere.

But try the Germans would. When the Wehrmacht launched its lightning attack of 1940, it achieved stupendous success; however, when it tried again in 1941, it suffered its first great military debacle in the snows of Russia. How and why did this happen?

III: Why Did Hitler Invade the Soviet Union in 1941?

The explanation that Tooze offers for Hitler's decision to go to war in 1939 was essentially one of military necessity driven by Germany's material weakness. Despite all the resources poured by the Third Reich into military spending, it was bound to lose the arms race against such economic juggernauts as the United States and the British Empire. It thus had nothing to gain by waiting.

The explanation he presents for Hitler's decision to invade the Soviet Union in June 1941 is in fact rather similar; his material position was weakening and he had to do something about it. This might seem odd given the fact that by mid-1941 the Third Reach and its allies were in control of virtually all of continental Europe. With these newly acquired resources at its disposal, one might except Nazi Germany to have been in a far more advantageous position. Yet it still faced economic difficulties that exacerbated the threat posed by the two great powers still in the game: Britain and America.

And serious this threat was. Though the German army had proven itself a formidable fighting force in continental Europe, it could alas not be deployed against the British Isles; only the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine could do the job, though ultimately they were no match for the Royal Air Force and the Royal Navy. It is true that Britain also lacked the capability at this stage to amount an effective offence, aside from establishing a naval blockade of Germany's new continental empire. However, what mattered was that it was still in play, and while this was the case, the United States would have a means through which it could "project its awesome industrial power against Nazi Germany" (p.402).

By mid-1940, fearful of German domination of Europe and backed by a bi-partisan majority in Congress, the Roosevelt Administration was already taking steps to realise America's potential as the world's pre-eminent military superpower. On 16th May 1940, as the Western campaign was underway, Roosevelt put a proposal to Congress to create a manufacturing base capable of supplying the United States with no less than 50,000 aircraft per year (in fact, in 1944, US manufacturers produced an astounding 96,270 aircraft, of which 74,564 were combat aircraft). Then, on 19th July, Congress enacted the Two-Ocean Navy Act, which committed to expand the size of the US Navy by 70%, calling for the procurement of no less than 18 aircraft carriers, 115 destroyers and 15,000 aircraft. In addition, on 16th September, Congress enacted the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, instituting America's first ever peacetime draft, designed to raise a fighting force of 1.4 million men. As a result, though America was a nation still at peace it was, by mid-late 1940, producing almost as much weaponry as either Germany or Britain (p.403).

Thus, Hitler clearly had something to worry about. America was a nation that was clearly gearing itself up for war, and it didn't stretch the imagination to ponder just who this immense mobilisation might be directed towards (a reality made all the more clear by gratuitous American material aid to Britain from March 1941 onwards under its "Lend-Lease" policy). Nazi Germany's new European empire thus needed to counter this mobilisation with a renewed effort of its own. However, the required results were not forthcoming.

The issue was that despite Germany's newly conquered territories providing it with "substantial booty and a crucial source of labour", they could still not match the raw-material abundance and industrial capacity of the Anglo-American alliance. Whereas the territory of the Allies was "energy rich", Germany's European empire was "starved of food, coal and oil". Germany's lack of usable oil had long forced on it a dependence on imports from Romania, as well as the production of synthetic fuels at high cost. This dependency was not solved by Germany's territorial acquisitions in 1940 - it fact it was made worse: the addition of fuel stocks in the West could not compensate for that fact Germany had now "added a number of heavy oil consumers to [its] own fuel deficit", meaning that "Germany now had to supply not only its own needs, but those of the rest of Western Europe as well" (p.411).

The result was that Germany's empire now in fact faced a severe shortage of oil, such that it could never revive the industrial activity of countries such as France to their pre-occupation level. Indeed, the effect of the German occupation was to "throw France back into an era before motorization". Meanwhile, Britain's global reach and naval control of shipping lines meant that it had a much enhanced ability to import oil. As a result, whereas in January 1941 Germany possessed stocks of barely more than 2 million tons, in London, the "alarm bells went off whenever stocks fell below 7 million tons". In fact, so great was the disparity that Britain's Ministry of Economic Warfare "had difficulty believing its highly accurate estimates of German oil stocks". To the British, it seemed "implausible that Hitler could possibly have embarked on the war with such a small margin of fuel security, an incredulity shared by both the Soviets and the Americans, who agreed in overestimating Germany's oil stocks by at least 100 per cent" (p.412).

The coal situation was similarly dire; in the case of coal, the absolute deficit of Germany's empire was small compared to total output, but the problem lay in its distribution from source to wherever it was needed most. Before the war, many European countries had imported substantial amounts of coal from Britain - now clearly not an option. These deficits now had to be covered by Germany's huge coal reserves in Silesia, the Ruhr, Belgium and northern France. One major problem, however, was transportation, especially after the Wehrmacht requisitioned much of Western Europe's high quality rolling stock. The result was a shortage of coal in many regions, which exacted a toll on heavy industry. In the case of France, which depended on 30 million tons of imports to cover 40 percent of its requirements, the total quantity of coal available was cut to half its pre-war level, precipitating a plunge in France's production of steel (pp.413, 415).

At the same time, the production of coal was heavily dependant on the supply of another crucial resource: food (Tooze notes that "there was no industry in the 1940s in which the correlation between labour productivity and calorific input was more direct than in mining"). Yet after 1939, the food supply in Western Europe was "no less constrained than the supply of coal". In a similar vein to coal, the issue was that the dairy farms of France, the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany itself were highly dependent on imported animal feed. However, imports of grain - which were sourced mostly from Argentina and Canada - were choked off by the British blockade, a problem that affected imports of oil seed as well. Furthermore, though France was itself a major producer of grain, these grain yields depended on nitrogen-based fertilizer (the same as situation as in Germany), which could be supplied only at the expense of explosives production. The scarcity of fertilizer and animal feed precipitated a "Europe-wide agricultural crisis" by the summer of 1940, with France experiencing a grain output less than half that which it achieved in 1938. As a consequence, rations both in Germany and in occupied territory had to be limited: in Belgium and France, they amounted to as little as 1,300 calories a day; in Norway and the Czech territories, they hovered around 1,600 calories a day - an obvious recipe for discontent (pp.418, 419).

Hence, the combined effect of the British blockade and the German occupation had turned the Western European countries - formerly a "formidable economic force" - into a "basket case", a "shadow of their former selves" (p.419). Germany's European empire was not, therefore, the "self-sufficient Lebensraum of which Hitler had dreamed" (p.420). In fact, it was dependant as ever on Nazi Germany's new ally, the Soviet Union.

The Nazi-Soviet rapprochement of 1939 raised the possibility of strengthened economic relations, a trend that culminated in the German-Soviet Commercial Agreement signed on February 11th, 1940, in which the Soviets committed to provide Germany with raw materials in return for German deliveries of machinery and manufactured goods. As such, according to German figures, in 1940 the Soviets provided no less than 617,000 tons of oil products 820,800 tons of grain and 846,700 tons of wood products.

The key point here is that, as Tooze puts it:

"In the short term the only way to sustain Germany's Western European [empire] at anything like its pre-war level of economic activity was to secure a vast increase in fuel and raw material deliveries from the Soviet Union. Only the Ukraine produced the net agricultural surpluses necessary to support the densely packed animal populations of Western Europe. Only in the Soviet Union were there the coal, iron and metal ores needed to sustain the military-industrial complex. Only in the Caucasus was there the oil necessary to make Europe independent of overseas supply. Only with access to these resources could Germany face a long war against Britain and America with any confidence" (p.420).

One way of achieving access to these resources was to maintain strong relations with the Soviet Union and forge some sort of 'continental bloc' to challenge the Atlantic bloc formed by Britain and the United States. However, this idea never enjoyed majority support in Berlin. The problem was that, given Germany's extreme material dependence on the Soviet Union, the Third Reich was always bound to be relegated to the status of a junior partner, with the kind of "humbling dependance that Britain now occupied in relation to the United States" (p.422). This degree of subordination on the Soviets was unacceptable, especially given the "subhuman" status attributed to Slavic peoples in Nazi ideology.

The second way was simply to invade the Soviet Union and take control of these resources directly. This was Hitler's preferred choice, cemented when he ordered the Wehrmacht to start preparing for such an invasion as early as July 31st, 1940. On this date, in a conference at this Obersalzberg residence, Hitler described the conquest of the Soviet Union as the key to ultimate victory in the war as a whole; its destruction was a necessary prelude to defeating Britain and neutralising the support of the United States. In his words, "Britain's hope lies in Russia and the United States. If Russia drops out of the picture, America, too, is lost for Britain, because elimination of Russia would tremendously increase Japan's power in the Far East", an allusion to the long-running competitive dynamic between Japan and Russia in Northeast Asia, which had previously culminated in a war in 1904. Russia was therefore the "Far Eastern sword of Britain and the United States", pointing squarely at Germany's ally, Japan. The defeat of the Soviet Union would therefore amplify Japanese power in the Pacific, at the direct expense of the United States (the US and Japan shared yet another competitive dynamic). Even if the United States decided to join the conflict, control of the immense resources of the Eurasian landmass would make Germany ready for this "war against continents" (p.424).

So now we have two components of an explanation for why Hitler chose to invade the Soviet Union. Firstly, Germany's European empire was simply not sufficient to mount a challenge to the "industrial strength looming on the other side of the Atlantic" (p.425). The Third Reich was bound to see its relative position decline, and this would end in eventual defeat. The only way out was to secure the resources of the Soviet Union. Moreover, the strategic gains that such a conquest would achieve would put Germany at an excellent position to wage war against both Britain and the United States, especially in concert with a strengthened Japan.

The third element relates to the stunning success achieved by the Wehrmacht in the spring of 1940 in Western Europe. The German army had "proved its ability to achieve decisive victory against what were thought to be the strongest armies in Europe" (p.425). The sense of confidence that swept the Wehrmacht in the aftermath of its lightning war emboldened it to try the same trick against the Soviet Union in the East. What happened in 1940 had been improvised, but now the tactics of lightning speed and concentration of force would be applied again, this time with preparation. As Hitler stated in November 1941, speaking of the invasion of the Soviet Union, "I have never used the world Blitzkrieg, because it is a very stupid word. If it has any meaning in regard to one of the campaigns at all, then it would have to be this one".

Given these three reasons to launch a war in the East, there was certainly no time to waste. However, as we know, things did not turn out as Hitler had expected. By issuing the order to invade the Soviet Union, Hitler had indeed "ushered in his own destruction", as the Wehrmacht was "bled dry" by a Red Army that was to play the greatest part in its destruction (p.429). How did this come to be, and was it inevitable?

Source: Never Was Magazine

Axis control at its greatest extent, before the Soviets would turn the tide in late-1942/early-1943. Germany's conquest of its Western European empire was impressive, but it ended up handing to Germany some coal-, food- and oil-deficit territories.

IV: Why Did the Germans Fail on the Eastern Front?

Was the Germans' failure to defeat the Soviet Union in 1941 an outcome bound to happen, or was it somehow their 'fault' for not fighting the war in the way they should have? Tooze introduces this question by citing John Kenneth Galbraith - the celebrated Canadian-American economist - who in 1945 claimed that "the simple fact is that Germany should never have lost the war". According to Galbraith, the Wehrmacht failed because the Nazi leadership had "failed to mobilize the German economy sufficiently" to support it, a mistake borne of a "mixture of overconfidence and incompetence compounded by a chronic lack of political will"(p.429). By now, one would be able to guess that Tooze disagrees with this voluntarist reading of events. It was not a "lack of political will" that cost Germany the war in the East, but rather, current military-economic realities and the decisions they wrought.

The first point to be made is that, in fact, considerable preparations were made in anticipation of the invasion of the Soviet Union - codenamed "Operation Barbarossa" - all throughout late 1940 and early 1941. Between May 1940 and June 1941, the army expanded from 143 to 180 divisions. In this time, the army also doubled the number of its tank divisions from 10 to 20, with a corresponding two-fold increase in the number of half-tracks (used for transporting infantry). The German army that swept into the Soviet Union in June 1941 was thus far more motorised than that which subordinated Western Europe a year prior (though it must be said that in 1941, three-quarters of the German army still relied on "foot and horse", p.433, 454). There were similarly spectacular increases in the output of artillery pieces, aircraft, anti-aircraft guns and U-boats. One is led to conclude that the Third Reich was, in fact, very successful in triggering a "very substantial further mobilization" of the German war economy in preparation for Operation Barbarossa (p.432).

Furthermore, the Wehrmacht launched the invasion with the element of surprise on its side - Stalin was apparently so shocked when he learned of Hitler's betrayal that he suffered a nervous breakdown. To add to this, the German army that invaded the Soviet Union probably outnumbered the unprepared Red Army troops stationed in the western sectors. Indeed, the force that Hitler moved into the East was gargantuan: 3,050,000 men advancing along a front stretching more than 1000 kilometres - the largest single military operation in recorded history (p.433, 452). Why was this not enough?

The most salient reason appears to be that the fundamental premise on which Operation Barbarossa was based - that the Wehrmacht could defeat the Red Army in a swift, decisive blow - was in fact wildly overoptimistic.

Barbarossa required a swift conclusion for a number of reasons. The first is that, from its conception, the conquest of the Soviet Union was always meant as a "means to the end of consolidating Germany's position for the ultimate confrontation with the Western powers". The final battle lay not in the East but in the West, where Britain and America were biding their time to construct truly fearsome war machines. If the purpose of Barbarossa was to give Germany the material means to challenge this growing threat, then it would have to be finished quickly. Hitler was thus driven to adopt a comprehensive, fully-fledged "Blitzkrieg strategy", an unprecedented "synthesis of campaign plan, military technology and industrial armaments programme" designed to knock out the Soviet Union as quickly as possible (p.430). It was the victory in the West - and the Nazis' racist condescension of the Slavs - that convinced Hitler that the Red Army could be brought to heel in this manner.

The second reason was that, as time passed and the Red Army got its act together after the initial shock, the Wehrmacht would face a progressively deteriorating situation. In a long-run battle, it was the Soviet Union that held the advantage. The population of Germany was likely roughly half that of the Soviet Union in 1941 (approximately 85 million vs 170 million). In contrast to the Germans, who had "conscripted virtually all their prime manpower", the Soviets were capable of drawing on this immense pool to call up millions of reservists. It was thus imperative that the Wehrmacht not be sucked into a long-run battle of attrition (p.452).

Furthermore, the "enormous expanse" of Soviet territory, coupled with the "sheer impassability" of the terrain, dictated that should the Red Army be allowed to withdraw to safe positions in the interior, this would present the Wehrmacht with "insuperable problems" (p.452). Not only would the Germans now face the challenge of operating at great distances from own their territory; they would also have to reckon with an enemy force backed by the great industrial might of the Soviet Union.

It is true that at this point, Germany's was a much more developed economy, with a per-capita GDP two and a half times that of the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, Stalin's Five-Year plans had brought massive advancements to the state of Soviet industry, comprising what Tooze refers to as "the first and most dramatic example of a successful developmental dictatorship" (p.511). He cites estimates according to which Stalin's regime was able to increase total industrial output 2.6-fold between 1928 and 1940, with armaments output increasing vastly more. Despite much of this industrial investment being concentrated in Western economic zones vulnerable to German attack, the First Five Year Plan (1928 - 1932) also established "a new Soviet industrial base, safely to the east of the Urals [Mountains], which had the capacity to sustain a self-sufficient population of at least 40 million people" (p.456). Even if Germany were able to overrun much of the Western Soviet Union, the Red Army would still be capable of drawing on a substantial degree of industrial capacity.

Add to this the critical raw-material situation in which the Third Reich found itself prior to Barbarossa. It was due to raw material shortages that Hitler perceived the need to invade the Soviet Union in the first place. Yet, how could Germany sustain a drawn out effort against a Soviet Union much better endowed in raw materials such as oil if by the end of 1941 the Wehrmacht could be "considering demotorization as a way of reducing its dependence on scarce oil" (p.455)? The conclusion was inescapable: as in 1940, the enemy would have to be smashed in the first few weeks or months.

However, the problem with counting on a swift victory was that "if the shock of the initial assault did not destroy Stalin's regime ... the Third Reach would find itself facing a strategic disaster" (p.460), an inadequately anticipated situation that, in the end, was exactly what came to pass.

The "Blitzkrieg" offensive planned for June 1941 consisted of a "massive central thrust towards Moscow, accompanied by flanking encirclements of the Soviet forces trapped in the north and south, [which] would allow the Red Army to be broken on the Dnieper-Dvina river line [along which runs the Dnieper in the south and the Dvina in the north] within 500 kilometres of the Polish-German border”. The Dnieper-Dvina line was critical because beyond that point, the Wehrmacht would begin to suffer from logistical constraints. Based on their experience in France, the Wehrmacht’s staff calculated that the “efficient total range” of their transport trucks was 600 kilometres, yielding an “operational depth” of 300 kilometres. Beyond the point, they would end up using so much of the fuel they were carrying so as to so become an inefficient means of transport. The extra 200 kilometres to the Dnieper-Dvina line would be covered by creating intermediate dumps of fuel and ammunition between German-occupied Poland and the front line. One fleet of trucks would ferry supplies to the dumps; another fleet, to the front-line troops. This constraint was so vital that army chief of staff Franz Halder, in his diary in January 1941, wrote that the success of Barbarossa depended on “Speed! No stops! Do not wait for railway! Do everything with motor vehicles … no hold ups … that alone guarantees victory” (p.453).

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Germany's gargantuan invasion of the Soviet Union. Army Group North, commanded by Field Marshall Wilhelm von Leeb, was tasked with invading the Baltic and capturing Leningrad. Army Group Centre, commanded by Field Marshall Fedor von Bock, was tasked with the invasion of Belorussia, then the capture of Minsk, Smolensk and Moscow. Army Group South, commanded by Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt, was tasked with invading the Ukraine (the bread basket of the Soviet Union) and securing the Crimea.

If, however, the Red Army were to escape destruction on this line, the Wehrmacht would face an entirely new set of problems. It would not be able to engage in hot pursuit, because it would need to establish forward bases with which to replenish the front line with fuel and ammunition. The only other alternative was to rely on the Soviet railway system, a dubious proposition given that this railway system, even if captured intact, was “insufficient to support the German army”. In any case, the Red Army had become “extremely proficient at evacuating rolling stock and sabotaging bridges, tracks and other railway installations”. As a result, the Wehrmacht had to make do with only 30% of its requirements in railway capacity. In this scenario, the German nightmare of a prolonged war in the East would become inevitable (p.454).

As it happened, the course of events would reveal this plan to have been excessively optimistic. By the end of July 1941 (about a month into the operation) all three German army groups (North, Centre and South) had “reached the feasible limit of their supply system” and were thus forced to halt their advance hundreds of kilometres west of the Dnieper-Dvina line (only Heinz Guderian made it to the line, but he found himself so exposed and cut off that he was all but vulnerable to the Red Army’s savage counterattacks) (p.487).

The Wehrmacht’s military crisis drove Field Marshal Feder von Bock – commander of Army Group Centre – to confide in his diary, “How a new operation is to start from this position with the slowly falling combat value of the troops, who are attacked again and again, I don’t quite know yet … If the Russians do not collapse somewhere soon, then it will be very difficult before the winter to hit them so hard as to eliminate them”. Meanwhile, Franz Halder admitted in his diary that “the Russian colossus, which had prepared itself for war with all the uninhibitedness that is characteristic of totalitarian states, has been underestimated by us … At the start of the war we reckoned with about 200 enemy divisions. Now we have already counted 360 … And when a dozen have been smashed, then the Russian puts up another dozen” (in fact, by the end of 1941 the Red Army had fielded no less than 600 divisions) (p.488).

Nevertheless, by late August, the Wehrmacht had again taken the initiative. On August 21st, Hitler “swung the main Panzer force of Army Group Centre southwards [towards the grain lands of the Ukraine] in a gigantic right hook … to produce what was arguably the greatest single German victory in the Eastern war”, encircling Kiev and opening the way for the conquest of the heavy industrial zone of the Donetz. In early September, Army Group Centre was ordered to begin planning for a renewed push toward Moscow – “Operation Taifun” – to begin in October (p.491).

At first, Taifun showed every sign of success. The Wehrmacht managed to inflict devastating blows, seizing six hundred thousand prisoners of war after a double encirclement at the towns of Vyazma and Bryansk. By the second week of October, Stalin’s regime came “close to breaking point”, as the population of Moscow was struck by panic over rumours that the Communist leadership was fleeing the city. However, order was restored, and General Georgi Zhukov managed to construct one more defensive line. Despite their losses, the Red Army managed to inflict on the Wehrmacht a heavy toll of their own. By October 8th, the autumn rains had begun, turning the central sector of the German army into an “impassable quagmire”. By the end of October, Army Group Centre was halted 100 kilometres short of Moscow (pp.492, 493).

By November, the fuel situation facing the German army was “rapidly approaching a critical point” – such that by early 1942 it would be “not the Russian mud but the exhaustion of Germany’s petrol supplies that would ensure the ‘complete paralysis of the army’” (p.493). The Panzer divisions had managed to fight their way to within sight of Moscow, but – at a distance of almost 500 kilometres from the forward supply dumps around Smolensk – they were simply unable to sustain a major offensive. Furthermore, assuming a quick victory, the Wehrmacht had made “no preparations … for active operations in the winter”, providing cold-weather stores only for a scaled-down occupation force (p.499). As a result, the cold was claiming tens of thousands of casualties; between December 1941 and March 1942, the Germans would lose 380,000 men to illness and frostbite alone (pp.500, 501).

By early December, Zhukov had managed to build an offensive force strong enough to mount a counterattack. Assured by intelligence that the Japanese intended to honour their neutrality pact with the Soviets (signed on April 1941 and binding until April 1946), the Red Army shifted a significant number of troops from Siberia and Russia’s eastern sectors to Moscow. Now under Zhukov’s command were 1.1 million men, 774 tanks and 1,370 aircraft, which he used to launch a surprise attack on the Wehrmacht’s Army Group Centre. In four months of intense fighting, the Germans suffered 420,000 combat casualties, in addition to the 380,000 from “natural” causes. It was only Stalin’s failure to concentrate his counterattack on Army Group Centre – instead opting to strike along the entire 1,500-kilometre front line – that saved the Wehrmacht from a far-reaching withdrawal. As a result, by March 1942, “with the Germans still lodged deep in the Soviet Union [100-150 kilometres from Moscow], the Eastern Front relapsed into relative calm” (pp.500, 501).

From a military perspective, the Wehrmacht and the Red Army had thus fought to a standstill. Yet, it was a situation that undeniably favoured the Soviet Union, which could now draw on its vast geographic depth and immense reserves of military-age men to make Germany's war in the East an ordeal like no other. Moreover, the Germans had now unleashed upon themselves the wrath of a fully-mobilised Soviet economy, which in 1942 and 1943 "considerably outproduced" that of the Third Reich (p.670). German armaments production eventually overtook that of the Soviet Union in 1944, but by then it was too late - the Anglo-American war machine was finally ready to enter the game for real.

Indeed, one major counterproductive consequence of the German invasion of the Soviet Union was to unite Roosevelt and Churchill more resolutely in their efforts against the Third Reich. In February 1941, the United States had already began its policy of Lend-Lease, lavishing copious amounts of material aid on Britain (throughout the entire war, Lend-Lease aid to the British Empire would total $31.4 billion, the largest recipient). One effect of Barbarossa would be to orient much of this aid - from both the United States and Britain - to the Soviet Union. In 1941, Allied shipments to the Soviets amounted to 360,778 tones of materiel. By 1942, this would balloon to 2,453,097 tons, eventually reaching a peak of 6,217,622 tons in 1944. The Soviet Union would end up being the second largest recipient of US aid, with $11.0 billion of materiel received throughout the war.

Yet, Lend-Lease was only the beginning. On August 14th, 1941, two months after the launch of Barbarossa, Roosevelt and Churchill released a joint statement eventually known as the "Atlantic Charter". This statement, which outlined American and British goals for a post-World War II world, essentially cemented the United States as the "centrepiece of the anti-Nazi coalition", throwing its weight fully behind the United Kingdom. The Nazi leadership interpreted it as "tantamount to a declaration of war" (p.501).

Furthermore, by mid-1941, the US navy was now "actively engaged in hunting down German U-boats in mid-Atlantic", as a strategy to shield the shipping lanes connecting the United States and Great Britain. In fact, so strategically important was the North Atlantic that on July 9th, Roosevelt announced that US troops would begin to administer the occupation of Iceland - taking over from the British who had invaded it in May 1940 to counter possible German influence in Iceland - a move that Hitler condemned as an act of aggression against Germany (p.501).

In addition, by October, the British and Americans had established a joint armaments-planning committee to begin work on a programme dubbed "the requirements of victory". The programme eventually called for the expenditure of no less than $150 billion (more than 500 billion Reichsmarks) over the next two years (1943, 1944) alone - more than the Third Reich was to spend on armaments throughout the entire war (p.501). Hence, by mid-1941, the United States was very much an active and energetic participant in the conflict, although it had not yet actually entered the war. It is possible that much of this activity was due to the sense of alarm triggered the German advance towards Moscow, and the realisation that it was in the East, rather than the West, that the most tremendous bloodletting would occur.

The requirements of victory: American armaments production would balloon throughout the first half of the 1940s to make the United States the world's premier military superpower, a status that it has held ever since.

Taken together, all of this suggests that Operation Barbarossa was a gamble that fundamentally involved enormous risks - both due to the ground realities of the battlefield, and the wider strategic context that surrounded it. Yet this time, unlike in 1940, the gamble would not pay off. In the West, the scale of operations never involved distances of more than a few hundred kilometres; in the East, the Wehrmacht faced a foe that controlled unimaginable expanses. The German army could thus never accomplish the quick, decisive victory that it needed. The result was a strategic disaster that loosed upon the Third Reich not only the Red Army, but also the military-economic resources of Britain and the United States.

Yet another consequence of the Soviets' dogged resistance was the frustration of Hitler's dreams of racially transforming the lands to Germany's East, of which one component was an atrocity for which the Third Reich shall forever be known: the Holocaust. Anti-semitism had long been a strain in Nazi ideology, but why did the Judeocide take on the horrendous and truly genocidal scale that it did?

V: Why did the Nazis Commit the Holocaust?

Tooze depicts the Judeocide as being deeply intertwined with the questions of labour and food; in that sense, the ideology of anti-Semitism could not be separated from economic considerations in explaining why the Nazis embarked on such an epically murderous programme of genocide.

After the Wehrmacht found itself halted by the tenacious defence of Moscow in the winter of 1941, the war in the East become one of savage attrition. Between June 1941 and May 1944, the Wehrmacht suffered, on average, 60,000 men killed every month on the Eastern Front, and even this paled in comparison to the last twelve months of the war (in June, July and August 1941 alone, with the Red Army's "Operation Bagration" underway, the Germans would lose about 590,000 troops) (pp.513, 514).

The problem was, by the start of Operation Barbarossa, the Germans were already "scraping the manpower barrel" - due to the small number of children born during World War I, Germany had "no option but to send virtually all its young men into battle" (p.437). Thus by the autumn of 1941 there were "virtually no men in their twenties who had not been conscripted" - in 1942, fresh teenager recruits were enough only to replace the losses inflicted by the Red Army (p.513). In the first half of 1942, this draft included at least 200,000 men taken from the armaments factories - a recipe for disaster at a time when Germany desperately needed to increase its armaments output.

One obvious solution to this conundrum was to enlist foreign slave labour. This was to be the task of Fritz Sauckel - the regional Nazi party leader in Thuringia - who was appointed as the Reich's general plenipotentiary for labour mobilisation in March 1942. In response to Germany's labour shortage he implemented "one of the largest coercive labour programmes the world has ever seen". By February 1944, the total number of foreign labourers would reach 7.9 million, constituting more than 20 percent of the German workforce (by June 1943, General Erhard Milch of the Luftwaffe could boast that the Stuka dive bomber was being "80 per cent manufactured by Russians") (p.517).

Yet this demand for foreign labour seemed to strike an "unresolvable contradiction" with the Nazis' programmes of genocide. The Holocaust claimed a stupendous number of victims - estimated to be roughly 6 million - and most of this killing occurred after the launch of Barbarossa, reaching peaks of intensity in 1942 and 1944. Moreover, the Wehrmacht also engaged in a policy of vicious maltreatment of Soviet PoWs (from which British and American PoWs were largely spared), which resulted in the deaths of 3.3-3.5 million prisoners from starvation and forced labour. Why would the Nazis carry out such large-scale programmes of annihilation if this would deprive them of a pool of potential forced labourers?

One answer is to frame this as a direct "compromise" between the contradictory imperatives of ideology and economics. While the former dictated the elimination of Jews and Slavs to clear out space for German settlement, the latter insisted on the requirement for foreign muscle to make up for Germany's labour shortage. Thus, in spite of the Nazis' genocidal tendencies, they had to keep the strongest Jews and Slavs alive to sustain their war machine. Tooze notes that given the strength of evidence accumulated in favour of the "compromise" interpretation, there could be "little doubt that it captures essential features of Nazi policy". The end result, given the fundamental importance of both racial struggle and the German war economy, was "a certain segmentation of policy, in which the SS was permitted to pursue the ideological imperative of exterminating the Jewish population" while the treatment of foreign labourers and a small segment of the Jewish population was progressively "'economized' to take account of the needs of the war economy" (p.538).

Tooze regards this as a "powerful interpretive framework" - however, its key weakness was that it ignored one additional factor that in 1941 was "an independent and powerful 'economic' imperative for mass murder": food (p.538).

The Nazis' preoccupation with Germany's food situation could be seen before the launch of Barbarossa, as they concocted grand designs for the future of the German-occupied East. As was discussed in Section III, the agricultural situation of German-occupied Western Europe dictated that the Third Reich either increase its dependence on the Soviets for grain deliveries, or seize their grain lands outright. The end-result of this line of thinking was to construct plans that would ensure that the Germans secure enough food from the Soviet Union post-invasion, even if this meant starving the occupied population to death.

One caught an early glimpse of how the Nazis might do this in their management of Poland. After the invasion of Poland in September 1939 by the Germans in the west and the Soviets in the east, the territory of the former Polish state was split into three: one part was annexed by the Soviet Union, another was annexed to Nazi Germany, and a third was managed under a German occupation regime known as the "General Government".

However, one challenge of administering this occupation zone was that, with Poland's best farming areas having been annexed to the Reich, the General Government in 1939 was "a territory of severe food deficit". The Reich was forced to support the General Government with deliveries of bread and grain in early 1940, but in order for the latter to achieve self-sufficiency, it was agreed that the grain available in the General Government would have to be "distributed strictly according to the needs of the German occupation". In practice, this meant constructing a "racial and functional" hierarchy according to which food was to be distributed (p.365).

At the bottom were the Jews. In the words of Hans Frank, head of the General Government: "I am not interested in the Jews. Whether or not they get any fodder to eat [fuettern] is the last thing I'm concerned about" (p.365). The second category was the Poles: "I shall feed these Poles with what is left over and what we can spare. Otherwise I will tell the Poles to look after themselves ... I am only interested in the Poles in so far as I see in them a reservoir of labour, but not to the extent that I feel it is a governmental responsibility to give them a guarantee that they will get a specific amount to eat". Above them came the General Government's Ukrainian minority, and then after that, the class of privileged Poles who "worked in important public services, such as the railways, or in factories producing for the German war effort" (p.366). At the top of the hierarchy were, of course, the German occupation authorities.